How will a new Trump administration prosecute corruption?

When the compliance lawyer Alexandra Wrage was invited onto CNBC’s program “Squawk Box” in 2012 to give an anti-corruption argument on the air, she was surprised. “I remember laughing at the time, saying, ‘Well, is there somebody that you found who’s going to give the pro-corruption argument?’”

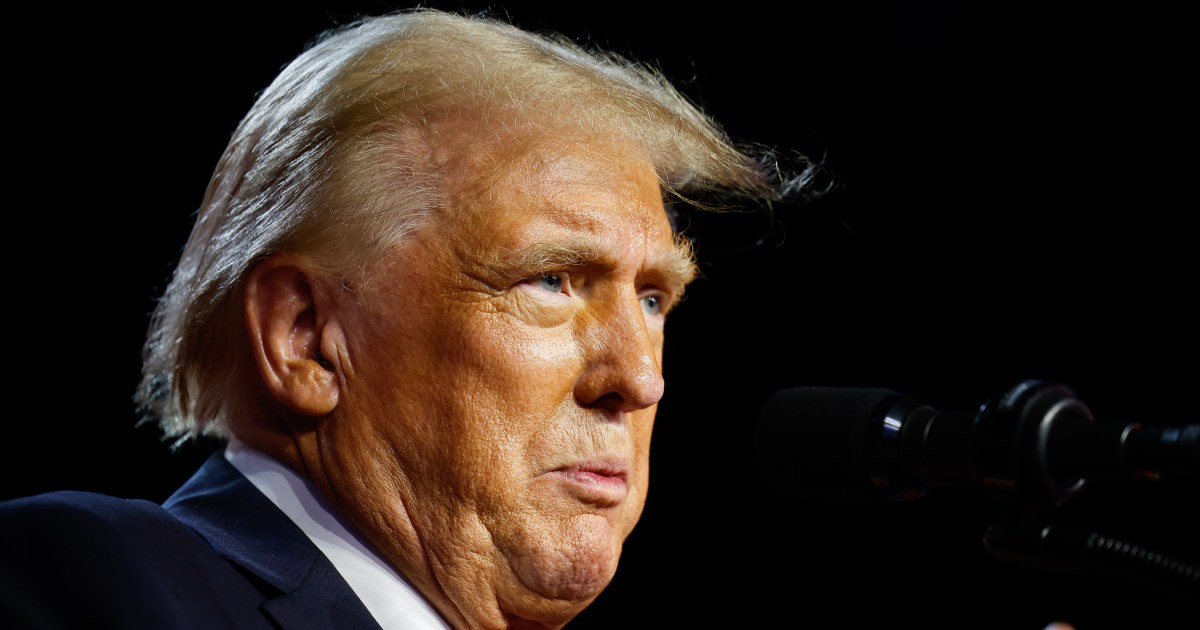

Whom they brought on was the president of the Trump Organization, four years before he won the presidency of the country the first time. Donald Trump called the United States’ Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, known as the FCPA, a “horrible law.”

Passed in 1977, the FCPA made it a crime for companies with a connection to the U.S. to pay — or even offer to pay — bribes to government officials of other countries. The law was the first of its kind in the world, and a landmark. Most countries have followed suit, adopting similar laws, although experts say many are not as aggressive in combating bribery as the U.S. statute.

“Every other country in the world is doing it. We’re not allowed to do so. It puts us at a huge disadvantage,” Trump said in that 2012 CNBC appearance.

Trump then hung up, and Wrage, founder of the anti-corruption organization TRACE International, replied to the host.

“Well, the answer is certainly not encouraging a climate of lawlessness. U.S. companies never benefit from lawlessness.”

As Trump entered the Oval Office in 2017, that memorable appearance resonated in the halls of the Department of Justice, which is tasked with enforcing the FCPA.

“We all wondered — what’s going to happen?” said Fry Wernick, supervisor of the Department of Justice’s FCPA unit at the time. As a result, he said, several pending corruption cases in the latter months of the Obama administration were wrapped up quickly before Trump took office.

A month into the first Trump administration, the president called in his newly confirmed secretary of state, Rex Tillerson, and reportedly shared his concerns about the FCPA, claiming it was unfair that U.S. companies could not pay bribes to secure business overseas.

News of this meeting quickly spread in Washington, and Wernick was pleased to hear that the secretary of state had set the president straight. Tillerson, who had previously served as CEO of ExxonMobil, “explained that ‘actually, no — the FCPA is a good law,’” Wernick said, recalling what he had heard about this private meeting. “‘It’s a law that helps balance the playing field for U.S. companies who are operating abroad. And, you know, it can actually be quite a useful tool.’”

Trump administration’s record of prosecuting corruption

Whether it was that discussion with Tillerson or other factors, the Trump years “turned out to be probably the most robust four years of FCPA enforcement ever,” according to Wernick. “More and more resources ended up going into the FCPA unit.” Fears about the first Trump administration being soft on corruption were overblown.

According to Wernick, the number of prosecutors in the DOJ’s anti-corruption unit nearly doubled during Trump’s first term, and the FBI’s International Corruption Unit established bureaus around the country and in foreign missions.

But Drago Kos, former chair of the Working Group on Bribery at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, said that while the first Trump administration met its international obligations to prosecute corruption, he fears that “this time, it may be different.”

“I’m not so much worried about the cases where the U.S. will not start the investigation,” Kos said, since allies could bring charges against corrupt companies under the United Nations Convention Against Corruption. “Much worse are the cases where the U.S. will start the investigation without having any reasonable grounds, because they will be pursuing other goals.”

Under the U.N. convention, each country’s leadership has discretion in how to apply anti-corruption laws, and Kos warned that means “the FCPA can be weaponized.”

In Russia, for instance, bribery charges have been used to go after President Vladimir Putin’s enemies. In 2003, Putin had Mikhail Khodorkovsky, at the time reportedly the country’s richest man, arrested on fraud charges and sent to prison for a decade — a move widely seen as retaliation for his opposition to Putin. Several other opposition leaders have been jailed for corruption, and last week, one of Putin’s top military officials, Maj. Gen. Mirza Mirzaev, was arrested on bribery allegations, making him the sixth military leader charged with corruption this year.

When Russian anti-corruption activist Sergei Magnitsky was arrested for tax evasion and died in prison, his business partner Bill Browder, the chairman of Hermitage Capital, took action by getting a U.S. law passed in his honor. In 2016, Congress passed the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act, which allows the government to sanction foreigners for human rights abuses, freeze their assets and ban them from entering the U.S.

As Trump first took office, just months after the passage of the Global Magnitsky Act, Browder was concerned the new administration might not use this powerful new law. But he was pleasantly surprised.

“One of the good things about the previous Trump administration was that he was very hands-off,” Browder said. “He had hired people who were all quite decent and who had the attitude to do whatever they thought was right.”

Browder fears that without those advisers around him, Trump may go in a different direction in his second term. “I think that they’re going to be very political about it. They’re going to choose their targets,” he said.

“What [Trump] cares about is protecting his friends like Mohammed bin Salman from Magnitsky sanctions when Jamal Khashoggi was killed,” Browder said, referring to the murder of the journalist that led to calls for sanctions against the Saudi crown prince. “The fear is that it becomes sort of inconsistently applied.”

Wernick, the former DOJ prosecutor, says he sees that executive discretion as an opportunity. “The world today is different than it was before. I think there’s an axis of adversarial nations right now,” he said, pointing to countries like China, Russia and Iran exerting their influences around the globe.

“All those countries I’m naming have huge corruption problems,” Wernick said. “Dictators and other leaders in these countries that don’t care that they’re stealing from their own people.” So, Wernick suggested, the U.S. could target adversaries with corruption charges, to complement sanctions.

“It never has been thought of in this way,” said Wernick, but “there’s an opportunity to actually use the FCPA thoughtfully in a manner that actually could be a useful complement to foreign policy efforts. … This is kind of an ‘America First’ approach that I would think the Trump administration could be quite receptive to.”

Much will depend on whom Trump puts in key leadership roles.

This week, the president-elect announced Sen. Marco Rubio as his pick for secretary of state. A co-sponsor of the Global Magnitsky Act, Rubio might be in a strong position to implement the law against corrupt foreign officials.

For attorney general, Trump has chosen Matt Gaetz. Trump announced his pick on the Truth Social network and said Gaetz would “root out the systemic corruption at DOJ, and return the Department to its true mission of fighting Crime.”

The Trump transition team did not answer questions about what kinds of crimes the new administration will go after, and if corruption prosecutions will be a priority.

“Personnel is policy,” said Wernick. “Who he has around him is going to matter.”