Fossil teeth hint at a surprisingly early start to humans’ long childhoods

An extended childhood, a hallmark of human development, may have gotten off to an ancient and unusual start.

One of the earliest known members of the Homo genus experienced delayed, humanlike tooth development during childhood before undergoing a more chimplike dental growth spurt, a new study concludes.

The fossil teeth of a roughly 11-year-old individual reveal slowed development of premolar and molar teeth up to about age 5, followed by speeded development of those same teeth. That slower start represented an initial evolutionary foray into extending growth during childhood, say University of Zurich paleoanthropologist Christoph Zollikofer and colleagues.

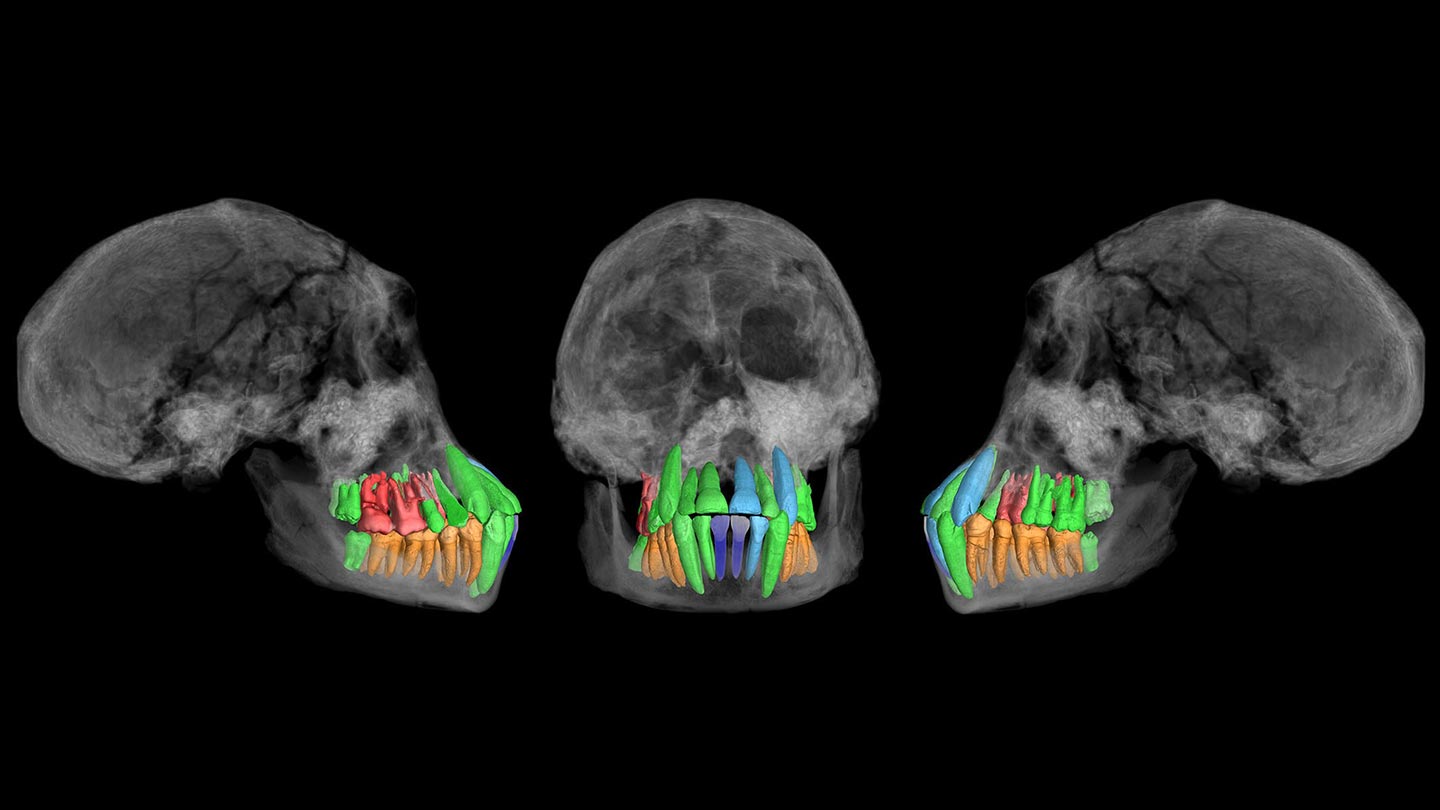

Their results, based on X-ray imaging technology that examined microscopic growth lines inside the fossil teeth, appear November 13 in Nature.

The youngster’s skull, along with four others unearthed at the Dmanisi site in the nation of Georgia, dates to between 1.77 million and 1.85 million years ago (SN: 4/8/21). While some researchers classify these fossils as Homo erectus, Zollikofer’s group regards the Dmanisi specimens as an undetermined Homo species. Homo sapiens originated much more recently, around 300,000 years ago.

Although a popular idea holds that a long childhood, slow dental development and an extended life span evolved along with brain expansion in H. sapiens, “that might not have been the case in early Homo,” Zollikofer says. Homo individuals at Dmanisi possessed only slightly larger brains than those of modern chimps.

Zollikofer’s team provides the first “fairly complete” reconstruction of an ancient hominid’s dental development, says paleoanthropologist Kevin Kuykendall of the University of Sheffield in England, who did not participate in the new study. Prior studies of ancient hominid dental development have focused on fossil individuals no older than about age 4, Kuykendall says.

X-ray imaging allowed the researchers to estimate the extent of tooth growth at different ages during the life of the Homo youth, who died just prior to reaching dental maturity between 12 and 13.5 years of age.

In contrast, dental maturity in people today occurs between age 18 and 22. Chimps reach dental maturity between 11 and 13 years of age.

If ancient Dmanisi individuals were our direct ancestors, then shared childcare including grandmothers and unrelated helpers may have spurred the initial evolution of a longer childhood, Zollikofer suspects. Much later, childhood growth slowed further as H. sapiens brains grew bigger.

If early Homo at Dmanisi belonged to a dead-end line, “then Dmanisi looks like a first evolutionary experiment with extended childhood,” Zollikofer says.

Those scenarios are possible, Kuykendall says. But finding that a slow start to tooth growth did not substantially delay dental maturity could instead denote one of many ways in which tooth development evolved among ancient hominids, including early Homo species that ventured into diverse habitats, he contends (SN: 2/18/15).

For instance, variations in available foods or age at weaning, rather than shared childcare, could have shaped dental development in early Homo groups, Kuykendall says.

Paleoanthropologist Tanya Smith of Griffith University in Southport, Australia, says the new study fails to show that the Dmanisi youth had an extended childhood. She points to the study’s estimate that the Dmanisi first molar erupted at around age 3.5, closer to that of chimps than humans. Prior studies indicate that the timing of first molar eruption strongly predicts many aspects of dental and physical development, putting Dmanisi on a chimplike trajectory, Smith says.

Chimplike dental features of the Dmanisi youth are consistent with that individual’s small brain size, an even stronger indication of rapid overall development, Smith says.

Source link