Britain debates new ‘assisted dying’ law

LONDON — British lawmakers voted on Friday in favor of a landmark bill that would for the first time help terminally ill adults end their lives.

The initial parliamentary vote in favor — 330 for and 275 against — starts months of debate and possible changes to the bill as it works through the House of Commons and the upper house of Parliament, the House of Lords.

If eventually passed, it will see the U.K. follow other countries such as Canada and Australia, as well as some U.S. states, and represent one of the most significant social reforms in a generation.

The bill would allow mentally competent adults in England and Wales with fewer than six months to live to request and receive help to end their lives.

Assisted suicide is currently illegal in Britain and carries a prison sentence of up to 14 years. That same sentence will remain for anyone found guilty of tricking, pressuring or coercing someone into making the choice if the bill is ultimately passed.

Debate around the contentious bill, which will continue to be discussed in Parliament in the run up to the vote, has prompted an uncommon outpouring of politicians’ emotions and moral persuasions in a political system where voting usually happens along party lines.

It has drawn comment from former prime ministers, religious leaders, judges and doctors, and shone a light on one of the few issues — birth and taxes perhaps being the only other two — that happen to everyone. The outcome of the vote looks to be uncertain given how many members of parliament have expressed their ambivalence on the issue.

Those in favor of the bill say such a law would relieve the unnecessary suffering of those with terminal illness and provide dignity and agency in a situation where the two are in short supply. Opponents say it could put the country on a slippery slope and place vulnerable people, such as the elderly or handicapped, at risk or put them under pressure to end their lives in order to not burden their loved ones.

Kim Leadbeater, an MP for the ruling Labour Party, proposed the bill, arguing it has “three layers of scrutiny.” Two independent doctors and a judge will be needed to sign off on any decision before the state allows a patient end their life.

One example of a similar law put forward by detractors of the bill is that of Canada, where government figures show that 4% of deaths are due to patients opting to end their lives. Euthanasia, which is also allowed in Canada and Netherlands and allows for doctors to give lethal injections, is different from assisted suicide and is not being debated in the U.K.

A 2023 government report showing figures from 2022 showed a 30% jump in the number of people choosing to end their lives, with more than a third of the 13,000 exercising their right saying their decision was partly due to feeling like a burden on loved ones. Canada currently plans to extend the law in 2027 to those whose sole underlying condition is related to mental health.

“There’s been lots of assurances about safeguards,” Gordon Macdonald, CEO of advocacy group Care Not Killing told Reuters. “But in every jurisdiction in the world where it’s happened, the safeguards have been removed or eroded over time.”

Even so, the U.K. bill has broad public support — a poll conducted last week by YouGov showed that 73% of the British public back the bill as opposed to 13% who said they don’t. While the current prime minister Keir Starmer has previously opposed assisted dying, he has not said how he plans to vote Friday.

Terminally ill broadcasting veteran Esther Rantzen, 84, has stage four cancer and has long supported a change in the law. “If I want assisted death, which I do because I want to have the choice, I will have to go to Switzerland… to achieve that,” she told Sky News.

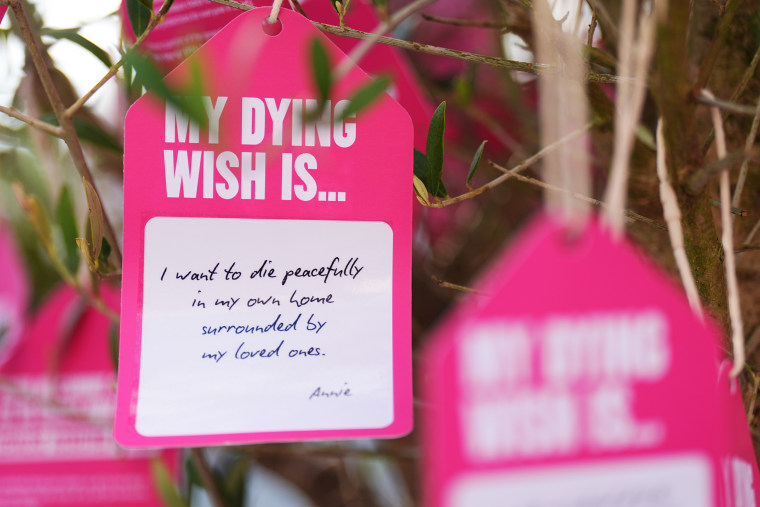

“I’m fortunate because I can afford to go,” she added, “but for all the hundreds of thousands of people in the future who can’t afford that and who want to die in their own homes surrounded by the people they love… they will have the choice if this law is changed and that would be a very good change.”

Former Labour Prime Minister Gordon Brown and three of his Conservative successors — Theresa May, Boris Johnson and Liz Truss — have all publicly come out against the bill. But former-Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron this week said that he had reversed his opposition to the U.K. bill.

Writing in The Times of London newspaper, Cameron said the bill specifically excludes mental health or disability grounds and that the safeguards contained in the bill will allow it to meaningfully reduce human suffering.

Cameron also refuted arguments — such as the one posed by the current health secretary Wes Streeting — that the expense and additional administration could add to pressure on the country’s beleaguered National Health Service. The former prime minister wrote that the bill would apply to a very small number of cases and that “the NHS exists to serve patients and the public, not the other way around.”