AI investments powering U.S. economic growth, but job creation remains uncertain

Increasingly, economic growth in the U.S. is being powered by artificial intelligence investments.

Today, many consumers directly interact with AI through applications like ChatGPT or through summarized search results on Google or Apple. They may also be encountering AI-generated images on social media.

But that’s not what’s driving the growth. Instead, it’s the investments in building out the raw computing power and electricity infrastructure needed to power those applications, and any that might evolve from them in the future. Think data center construction, computer processing chips, information processing equipment and electricity transmission hardware.

“Where AI has had a direct impact on the economy is in capital spending by [tech companies] and other companies on hardware and software necessary to expand their cloud-computing capacity so it can accommodate greater needs of demand for AI computing,” said Ed Yardeni, president of Yardeni Research, a market and economy consulting firm.

For now, the gains from this increased spending on AI tech and infrastructure have been relatively narrow both in terms of jobs and financial returns.

And yet the gains in the stock market have been massive. According to a new estimate by Skanda Amarnath, executive director of Employ America, spending on building up AI technologies made up between 16% and 20% of real gross domestic product growth in the third quarter of 2024 alone, and is only expected to grow. As a share of total spending outlays, AI-related investments are on track to surpass the share of GDP attributed to the late ’90s dot-com boom and become as large as housing was during the 2000s bubble, Amarnath wrote in a Bloomberg News article published Monday.

“We’re starting to see it show up in the data,” Amarnath told NBC News. “It’s something that means it’s more macro relevant, and will probably be a tailwind for growth in 2025.”

The technologists pushing the AI buildout are heralding AI not just as having the potential to transform business productivity, but as one of the most important developments in human history. For the moment, a “FOMO” mindset, not immediate profits, appears to be driving much of the current cycle.

“Superintelligent tools could massively accelerate scientific discovery and innovation well beyond what we are capable of doing on our own, and in turn massively increase abundance and prosperity,” Sam Altman, head of OpenAI, which built the original ChatGPT, wrote in a recent blog.

At the same time, a few scattered voices have already been referring to the current AI investment cycle as a “bubble” that, like the dot-com and housing ones, could burst and lead to a downturn.

“Over-building things the world doesn’t have use for, or is not ready for, typically ends badly,” Jim Covello, head of equity research at Goldman Sachs, said in a July report published by the investment banking giant. “The NASDAQ declined around 70% between the highs of the dot-com boom and the founding of Uber.”

In the meantime, though, high-profile AI-related announcements continue to pile up. On Tuesday, President-elect Donald Trump announced a $20 billion deal to build new data centers in partnership with a billionaire developer from the United Arab Emirates. Later that day, Amazon’s AWS cloud-computing group announced it would spend $11 billion on AI-related investments in the state of Georgia. Earlier this month, Microsoft announced it was spending a total of $80 billion on AI-enabled data centers for its fiscal 2025. And in December, Japanese conglomerate Softbank held a joint news conference with Trump to announce $100 billion on AI-related spending in the U.S.

The gains are also playing out in the stock market, which had a stellar 2024 thanks largely to the performance of the so-called Magnificent Seven. These seven tech firms — Amazon, Apple, Google parent company Alphabet, Facebook and Instagram parent Meta Platforms, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla — gained an average of 63% last year, with Nvidia surging a whopping 171%. Together, these companies now comprise one-third of the entire value of the S&P 500 index and accounted for more than half its gains.

“Just about all of them are viewed as an AI play in one way or another,” Yardeni said.

Last year, approximately a third of all startup investments went toward AI-related companies, the highest percentage on record, according to data from Crunchbase, which tracks venture capital data.

Besides tech firms, electricity companies and infrastructure providers have also seen their share prices soar. Firms benefiting from the run-up include Constellation Energy and Vistra, both of which are seen as specializing in nuclear power. Constellation announced last year it was partnering with Microsoft to restart one of the reactors at Pennsylvania’s Three Mile Island nuclear site.

One thing missing from the picture, for now, is a wave of new jobs — though some of the AI-focused investment announcements are promising tens of thousands of them will eventually come.

In fact, a critical premise of AI is its potential to automate human-centric roles, potentially leading to job losses. And while all new technologies end up creating some new occupations, they can also wipe out entire professions. Surveys have found numerous tasks, from writing to computer coding to illustrating to translating, that were once performed by people, are likely to be taken over by bots, if they haven’t already.

Instead, the most direct beneficiary from the current investment pulse, so far, has been the construction industry, which continues to see healthy annual job growth of more than 2.5%. Construction-related spending on data centers was up 43.1% from a year earlier, according to surveys tracked by the Associated General Contractors of America.

Employment in the utilities sector, too, is now at highs not seen in more than 20 years.

But other sectors that benefited from previous tech-led run-ups, especially professional and business services — namely, white collar work — have ground to a halt. Even traditional software engineering jobs are sparse: Job postings for those roles on Indeed have fallen back below pre-pandemic levels.

“It hasn’t created a huge employment boom,” Yardeni said. He continued: “AI increases the productivity of programmers, so maybe on balance we’re not going to see a big increase in the numbers of programmers hired to produce AI,” Yardei said. “The payoff will have to be on productivity.”

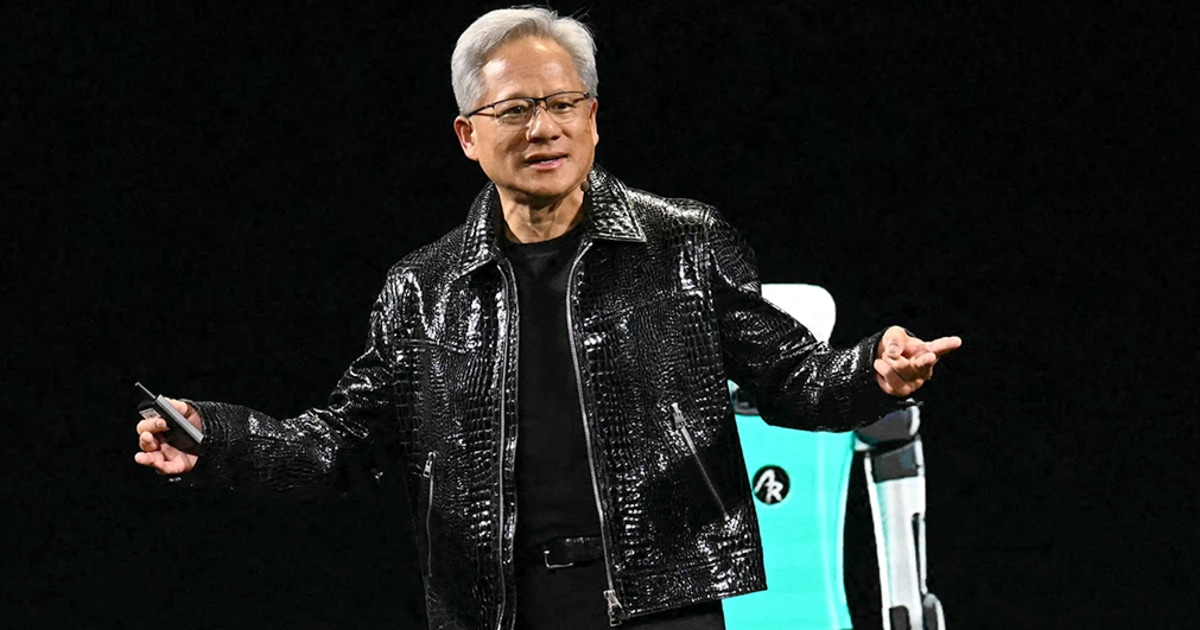

Still, for better or worse, the U.S. economy, not to mention the stock market, is increasingly riding on expectations of a payoff from AI. One financial executive recently summarized the outsized weight of AI on the economy in a tongue-in-cheek manner. “I jokingly say sometimes, we levered the entire retirement of America to Nvidia’s performance,” Marc Rowan, chief executive of Apollo Global Management, said at a company event this autumn, according to the Financial Times, referring to the chip-maker’s role in pulling stocks higher.

Indeed, some academics say that while there is wide agreement that AI bets will pay off eventually in terms of increased productivity, no one knows when, or how, an actual payoff to the public promised by increasingly sentient computers will occur.

“These investments are costs,” said Tania Babina, associate professor of finance at the Columbia Business School — meaning tech firms are making investments that they hope will be profitable down the line. “So hopefully the benefits will be broader in scale, and not just to these tech leaders.”